Why AI Needs Baby Jesus

Bear with me on this one.

Silicon Valley is obsessed with storytelling these days. Don’t believe me? Go open X. But first, come revisit yesterday’s weekly shop run with me.

I went grocery shopping with my two-year-old. She stomped through the supermarket like she owned the place, peeking behind every shelf, grabbing anything her little fingers could reach. Then she stopped in front of a life-sized Father Christmas and screamed in delight: “Grandpa!”

I laughed, picked her up, and tried to explain that this was not, in fact, her grandpa. Still: old man, beard - the deduction was not terrible.

I told her Christmas was coming. She asked “what Christmas?”, so I gave her the shortest version I could manage: we celebrate the birth of a baby, born far from home in a stable and laid in a manger.

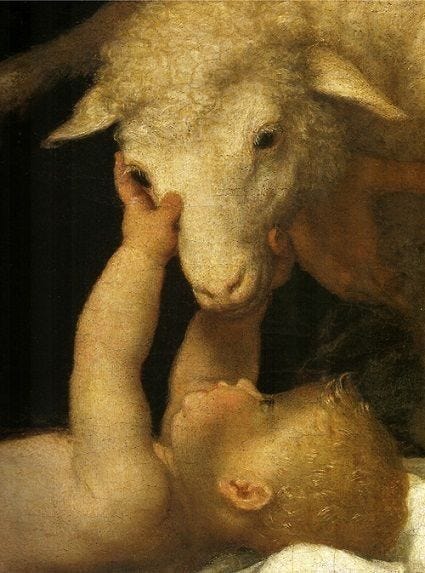

This story, the Nativity, is one of the most well-known stories in the world. We recite it to children from the youngest age. Somewhat irrespective of whether you believe in God or not, it is a story that makes you unequivocally root for Baby Jesus. Giving birth is an arduous ordeal, doing it in a stable is nothing short of absurd. Despite the uncomfortable fact of being laid in a manger, baby Jesus was a content little chum. We feel like he, Maria and Joseph deserve far more than they got and so naturally think it good judgement of the three wise men to bring gifts. The least they could do, really.

On the way home I kept thinking: What makes some stories stick in our minds while we forget others in the blink of an eye? Why do some stories make us root for people while others make us wish ill on them?

I am not alone with these thoughts. Recently, the tech world has been in a minor storytelling frenzy. It was catalysed by a Wall Street Journal article about how “companies are desperately seeking storytellers”, observing a rise in job postings looking for some variation of storyteller. Folks on X did what folks on X do: Many had opinions on the matter, from some feeling legitimised in their corporate media strategies, to others ridiculing that tech was rebranding the job of marketing and communications professionals, to yet others noting that tech has finally realised that social science and humanities graduates can add real value.

Rather than asking whether tech companies should hire storytellers or not, I am more interested in what makes for a great story in the first place. In the hunt for answers, at least three camps form.

The first treats storytelling as a box-ticking exercise: start a podcast, publish a newsletter, ship a launch video. If L’Oréal can do a Not a Beauty Podcast and Accenture can be Built for Change, then surely your enterprise software company can, too. Rather than asking what storytelling needs in order to be successful, this camp assumes that by throwing enough stories and paid ads to promote them out there, folks will eventually listen.

The second camp is that of the founder fundamentalists: it permits no outsourcing, ever. Great stories are an extension of leadership. Apple’s product stories worked because of Steve Jobs, not because someone ran comms well. You either have it or you don’t.

The third camp, the one I really care about, asks a more annoyingly difficult question: why should anyone care? A story is not content. Instead, it is a frame on human existence. It lives in the gap between what you believe about the world and what you want to awaken in someone else.

Stories are impactful when they feature relatable characters - flawed heroes or caring villains, when there is struggle and conflict, when the stakes are high and there is an emotional connection with the protagonists. A story works when it conveys an underlying meaningful truth about the world, and reveals it in a way that makes us rethink how we see ourselves or how we live our lives.

Communications expert Lulu Cheng noted that good stories make us root because the protagonist feels under-rewarded relative to what they deserve. Think Mary and Baby Jesus, Hänsel and Gretel, or Harry Potter: humble, outmatched, still trying. Our rooting becomes so fierce that we celebrate the absurd serendipity required to overcome their obstacles (defeating Voldemort at ages 1, 11, 13, 14, 15 and 16; killing a witch as a child; overcoming death itself). The story frames their potential relative to what they have today and makes our insides scream: they deserve MORE!

Bad stories do the opposite: When someone has too much relative to what they seem to deserve, the audience starts rubbing their hands in anticipation of blood. Stories badly done frame actual heroes in the way good stories frame villains. We watch, thrilled, for the fall.

In the tech ecosystem, bad stories focus too much on founders rather than users. Instead of framing the user as the hero, tech CEOs increasingly “cast themselves as the hero in their own story and, in doing so, risk becoming the villain in everyone else’s” (Ashley Mayer). Bad stories announce how many new AI billionaires were minted, in record time. Bad stories lean into world-domination theatrics without offering a convincing why.

As a consequence, people outside the AI industry feel that AI folks already have far more than they deserve. Alongside calls for regulation, some begin to stake their happiness in AI’s downfall, taking all its heroes with it. This helps explain the sabre-rattling around the AI bubble. People don’t just think it’s coming - they want it to come. In their eyes, everyone got way more than they deserved.

There is a different way. The founder of OpenEvidence - AI chat for doctors - revealed the story that motivates him and his team to work their hardest every day.

It’s the story of a doctor who, after starting to use OpenEvidence, saves enough time to go home for dinner with her family every night. Surprised and delighted to see her at the table, her son asks why she is home early. His voice cracking up, her husband replies: “Mummy gets to have dinner with us every night of the week from now on.”

While this may be overdoing it on the weepy tone, the point is that tangible impact for real users is what lets a story earn an emotional connection. Companies need to return to the question “why should anyone care?” From there, the stories almost write themselves. The nurse and the restaurant owner make for far better protagonists than ARR-hyped AI founders.

This current moment in AI, rather than deep religious fervour, is why I keep thinking about Baby Jesus. The Nativity reminded me of the power of simple storytelling. The Bible and Christian faith are among the most successful examples of storytelling ever. They did not rely on big budgets, perfectly lit studios, or fancy roles. They rest on clarity of purpose (God’s love for all people), a link to human betterment (hope and salvation), and a pursuit that rewards humility, making us root for the protagonists.

My daughter didn’t care much for the story yet - she was too busy throwing a pot of yoghurt on the supermarket floor. In time, she’ll get there.

This Christmas and as a resolution for the New Year, let our stories be less braggadocio and more Baby Jesus.

Fittingly, this story‘s storytelling is incredible! - great piece! :)

Great read.

Founder stories have their place, but with few exceptions the best brands know that the product is the stage and the user is the star.