Deadlier Sins

AI and the age of unproductive vices

One of the first convictions I formed as an investor was that the most successful consumer companies cater to the seven deadly sins: lust, gluttony, envy, pride, wrath, and sloth. From prostitution, often described as the world’s oldest profession, to modern brands like Instagram and OnlyFans, every era has found ways to monetise these drives. In fact, consumer businesses that do not tap into our vices almost never become truly successful.

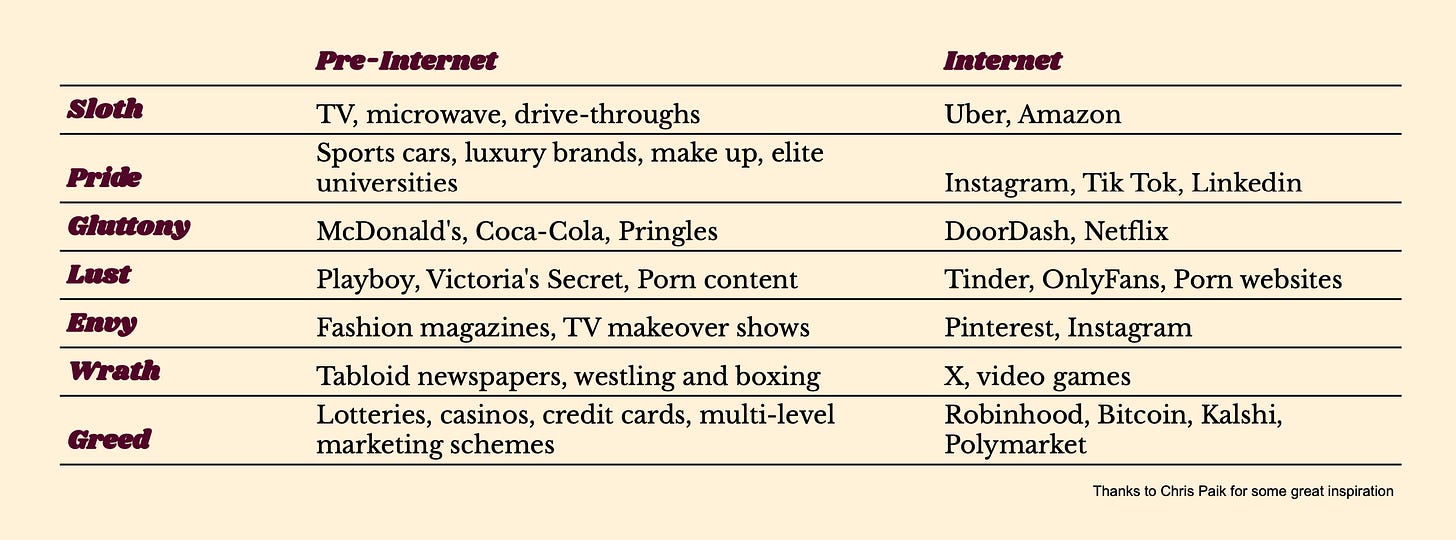

Before the Internet, each sin had its own industry, from fast food and porn to luxury brands or casinos.

The Internet added even more powerful solutions to the same desires through ride-haling and food delivery services, social media platforms, online betting markets, and even more porn.

This is less of a criticism than it sounds. The seven deadly sins are not merely old warnings about chastity and restraint - thou ought not to whore, drink or brawl - they also describe something essential, and often productive, about human nature.

Sins as productive motivators

Chris Paik reframed the seven deadly sins as humanity’s seven core motivators: “They are time-tested core motivators that incentivise people to do things.”

Each sin maps to a task required for human evolution. They are therefore drives that can be productive, or even required to survive, for the individual or group:

lust => reproduce

sloth => conserve energy

greed => secure resources

gluttony => soothe discomfort, overcome scarcity

wrath => reduce pain, fight off others

envy => drive to become better, adjust strategy to secure resources

pride => attract allies and mates

Throughout history, indulging a vice served at least some productive outcome. It forced us to develop skills, negotiate with others, face rejection, learn and adapt, only to yet again test ourselves against the world.

The commercial landscape reflected this. Rather than throwing humanity into a hellhole of sinful desire, companies that catered to our vices often also reinforced some productive individual and societal behaviours. Dating apps are built around lust and status signalling, but they also form social competence and increase matching efficiency. Luxury brands feed pride and envy, but they also fuel a desire to be successful, foster creativity, and sustain craftsmanship. Fast food and convenience food cater to sloth and gluttony, but also free up time that would have been spent cooking. Social media and tabloids fuel outrage and polarisation, but also expose scandals and help mobilise social or political movements.

We all live in Sin City now

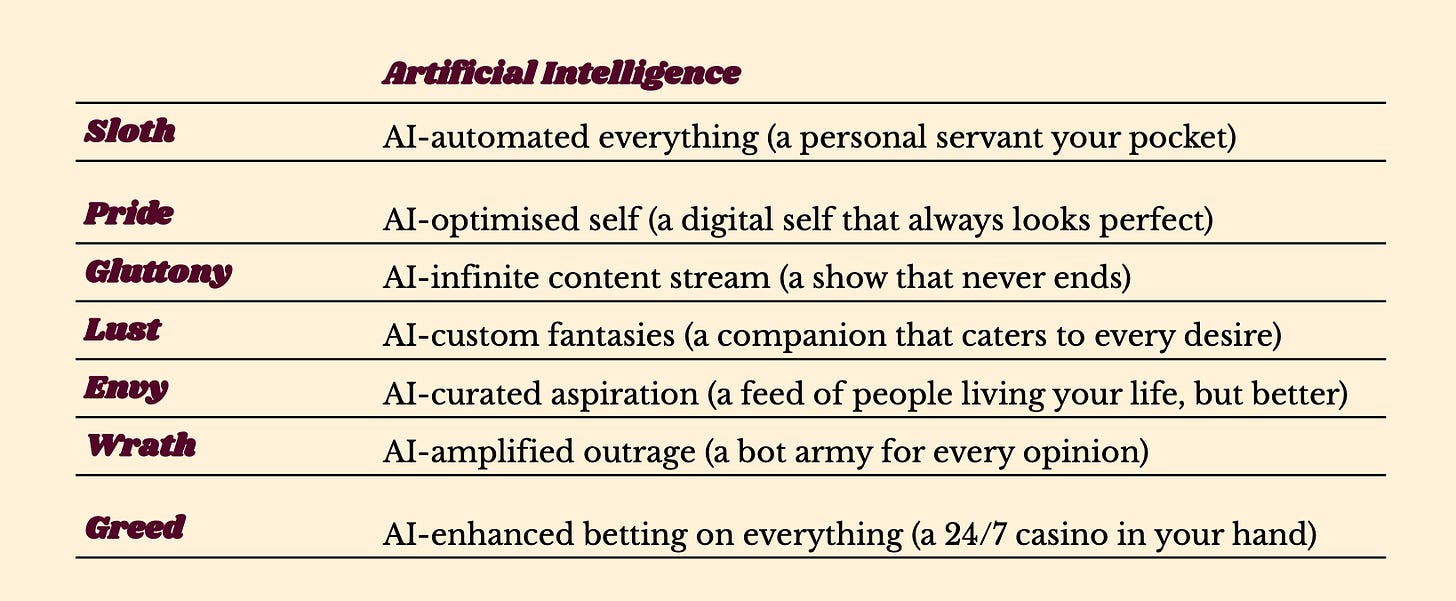

The current technological wave takes things one level further. AI now offers an even more powerful form of satisfaction: automated, individually optimised, and available around the clock. Everyone living inside their personalised Sin City. And, as in previous eras, each vice will be capitalised on by a new generation of products.

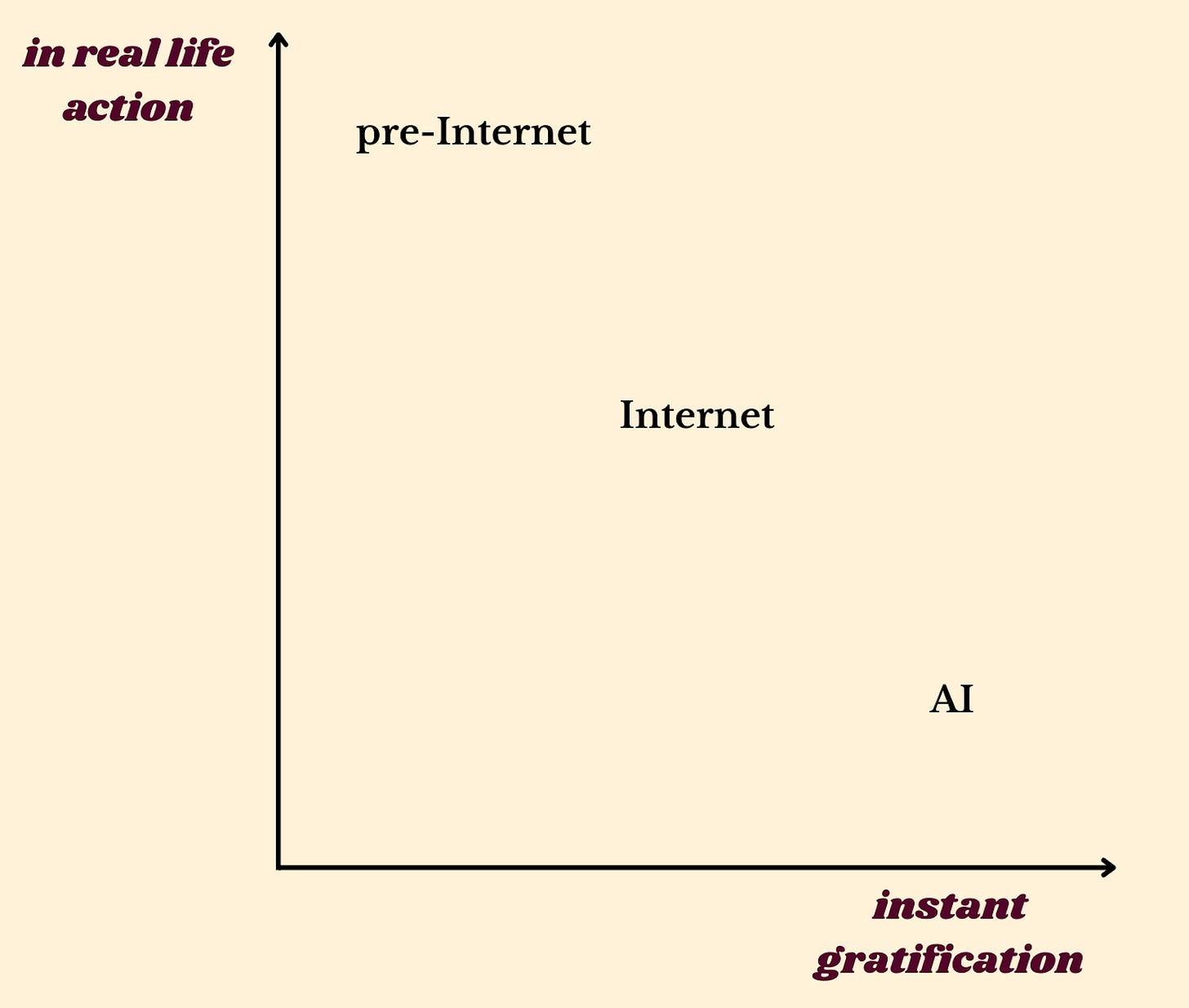

Decoupling desire from productive action

However, the difference to previous eras is that AI now threatens to sever the tie between our sinful drives and the real-world behaviours that make them productive. AI provides us with the gratification without requiring much action. Our ancient human drive remains but the productive pathway to satisfying it disappears.

AI companions provide boundless intimacy without any actual interpersonal discourse or empathy. Junior developers rely on AI autocomplete instead of learning programming fundamentals. Slop content is flooding social media in a push to gain status while driving little underlying human insight. People are editing themselves into imaginary scenes for social media they will never experience.

Retreating from the world

Where satisfying our vices previously pushed us out into the world and motivated us to build capability, AI is turning them into lonely ends in themselves. The signs are everywhere. We are drinking less, partying less and having less sex. With this decline of real-life sinning goes the loss of its productive by-products. People are entering fewer committed relationships, having fewer children, reading less, joining political parties less and doing less sports, especially the team sports that depend on social commitment.

The line between productive and destructive vices has always been thin. Industries built around greed, lust and pride have long carried serious harms, even without AI. But with AI, our vices are optimised past the point of any usefulness. The human striving that once pushed us into the world and bound us together weakens as desires are met instantly and in private.

Derek Thompson warns: “The future will be hot, high, and solitary.” AI enables us to receive satisfaction completely by ourselves, upending the evolutionary function that once made these vices useful. When technology serves us that well, it stops serving us at all.

And so, the seven deadly sins may indeed turn out to be just that.

Inside the experience machine

The more perfectly AI works, the more we live inside the experience machine. Nozick’s 1974 famous thought experiment investigates hedonism, the idea that pleasure is the only intrinsic good, by asking whether you would plug into a machine that can simulate any pleasurable life while you float in a tank, unaware that none of it is real. Most people said they would refuse. They seemed to care not just about feeling good, but about actually doing things, becoming a certain kind of person, and staying in contact with reality rather than a convincing copy of it.

Fifty years later, we are already partly living in Nozick’s experience machine. If it is difficult for us to get away from our phones, it will be near impossible for us to walk away from ever more powerful pleasure machines. As hedonistic technology approaches its most powerful form, it strips away friction and turns us into willing prisoners.

In their 1976 song “Hotel California”, The Eagles addressed the dark side of capitalism, hedonism, and excess. Today, the lyrics feel uncannily prescient, especially if one reads “device” not metaphorically but literally.

Mirrors on the ceiling, the pink champagne on ice

And she said, “We are all just prisoners here of our own device.”

And in the master’s chambers, they gathered for the feast

They stab it with their steely knives, but they just can′t kill the beast.

Last thing I remember, I was running for the door

I had to find the passage back to the place I was before.

“Relax,” said the night man, “We are programmed to receive.

You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

Turning the tides

Once we recognise ourselves as willing prisoners of ever more perfect pleasure machines, the question becomes how, or whether, we choose to escape. What is the counter movement to an AI-induced desire nirvana? Two paths are opening up ahead of us.

The first takes us down a conservative and Luddite turn of society: reject the pleasure engine entirely. Avoid it like crack cocaine and return to purity instead. We are already seeing early signs, as Australia is moving to ban social media for children, while China has imposed strict limits on gaming and social media use for minors.

The second path does not reject pleasure and desire - it does the exact opposite. It radically embraces our wanting humanity: to laugh, laze, lust, argue, spite, and drink, but to do these things with other humans rather than machines.

In order to free ourselves from the machine, we need to double down on our real-world desires. Deep down, our bodies are still closer to the animalistic instincts of our ancestors than the technologies we will eventually merge with. Machines are hacking this instinctive system and using it to keep us hooked. It is time we instead become addicted to humanity again.

We’re only human after all

The world’s leading AI companies have long understood that radical humanity must be the ultimate positioning of AI technology. OpenAI and Anthropic focus their marketing on human craft, depicting a human-next-door using AI to solve problems or create joyful moments with friends in real life. Rather than simply smart marketing to ward off critics, they capture that embracing our humanity is how we continue to thrive as a species in the face of God-like technology.

Past eras rewarded those who could get the most out of their devices. The next will reward those who can keep their devices from getting the most out of them.

Time to be a bad girl.

Thank you for sharing. It reminds me of what (I believe) Edward Wilson said: the problem of humanity is that we have paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.

I think we’re living in times where technology is moving at a pace that humanity cannot fully embrace it at the speed is intended to move. Our intrinsic value is to be in community, yet while we are more connected than ever in terms of proximity, we find ourselves the loneliest we’ve ever been.